In the boundless realm of artificial intelligence, where algorithms craft music, create art, and write poetry, a complex and multifaceted question looms large: Who owns the creative output of machines? The intersection of AI and copyright law is an increasingly relevant topic that challenges our understanding of intellectual property in the digital age, and it also plays an integral role in the current WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes in Hollywood.

So, let’s delve into the emerging debates, the implications for creators and innovators, and the quest for balance between fostering AI innovation and protecting the rights of human creators.

Originality and Creativity

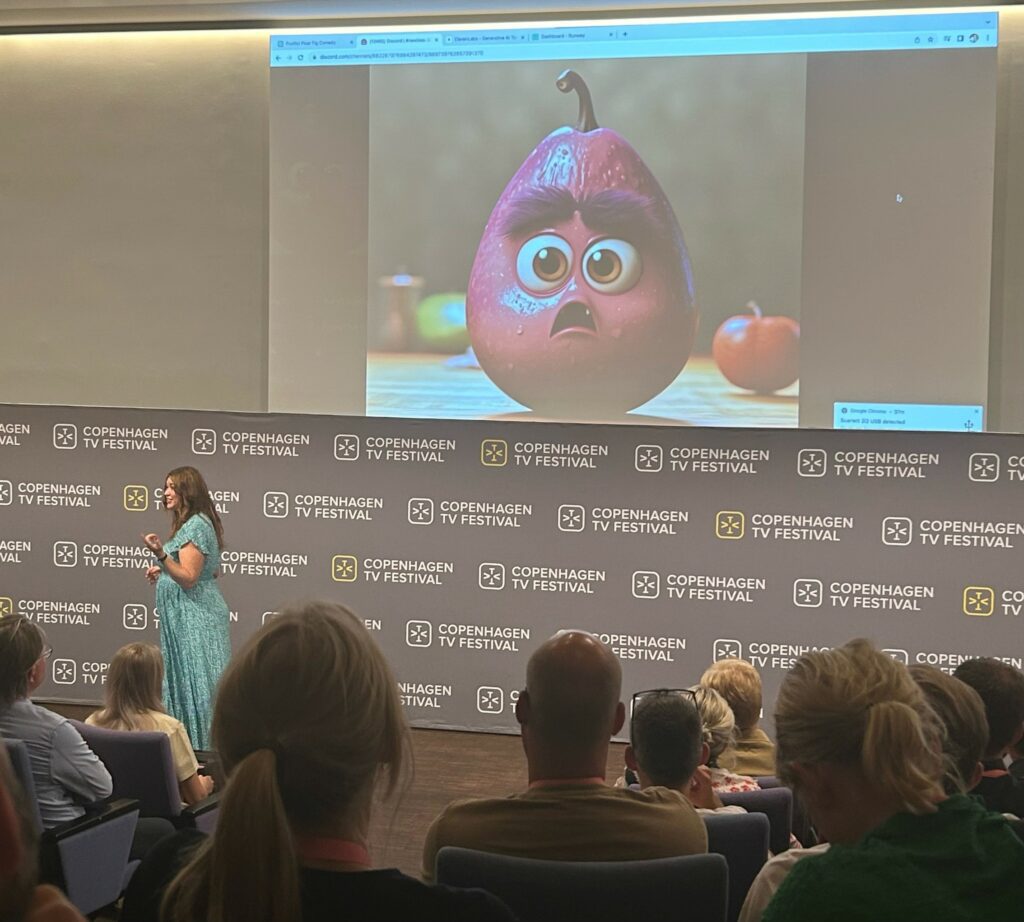

I recently attended a session at Copenhagen TV Festival called “AI – Friend or Foe?” by Danielle Lauren who is a Creative Innovation consultant for film and TV and the CEO of Future Proofing Storytelling. Danielle has always viewed technology through a creative lens, asking how this innovation can drive narrative, create closer connections to characters, or build fan engagement. In her talk, she helped break down both sides of the argument, showcasing the incredible creativity and efficiencies that lie within AI whilst questioning the real-world consequences for film and TV. How important this topic is for creatives was evident from all the participants who stood at the back and couldn’t get a seat.

Danielle started by stating: “We have an enormous challenge ahead to protect our storytellers, but we must find solutions that run in parallel with technological advancement. Never bet against tech, it always wins. The question we need to ask ourselves is – knowing that AI will inevitably be integrated into every aspect of our civilisation, how do we protect the heart and soul of our industry? We must take this seriously, the future of human creativity is on the line and that is worth fighting for.”

Generative AI is created from past content. Using already created works, AI makes predictions on what could be solutions to a request. Therefore, so-called large language models such as ChatGPT require vast amounts of information to train their systems and allow them to answer queries from users in ways that resemble human language patterns. According to Danielle, over time it can become extremely formulaic and repetitive, though. It relies on human ingenuity to stay interesting. “So, if we want to stay ahead, we really need to push our creative boundaries to manifest new, unpredictable, authentic, and human stories that are original and fresh. I assist storytellers with heightening their creativity, because if you’re just regurgitating what an AI chatbot can create then you’re not being original, interesting, or creative. I’m hoping AI will force a new era of hyper creativity.” – Danielle Lauren.

Questions regarding the originality and creativity of AI-generated works are central. Can AI truly create original content, or is it merely replicating patterns it has learned from existing works? The threshold of what constitutes creative and original work in the context of AI-generated content is a subject of ongoing discussion.

Authorship and Ownership

Another question is determining who should be considered the author and owner of AI-generated content. Should it be the human creator of the AI system, the person who trained the AI, the AI itself, or some combination thereof? And what about the used material?

During Danielle’s session, we also created a Pixar-like animated film with a fig as the main protagonist. ChatGPT wrote us a brilliant synopsis and script in the style of Larry David, Midjourney created an adorable still of our main character and Runway created a video snippet. And we did all of that within 15 minutes!

However, Pixar is a brand, of course, and so is Larry David. Therefore, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the copyright questions arise very quickly when it comes to AI-generated content. And we just have to look across the pond to understand what an existential threat AI poses for creatives. The WGA demands to “regulate the use of artificial intelligence on MBA (“Minimum-Basic-Agreement”)-covered projects: AI can’t write or rewrite literary material; can’t be used as source material; and MBA-covered material can’t be used to train AI.” While Fran Drescher, president of SAG-AFTRA, declared that “artificial intelligence poses an existential threat to creative professions, and all actors and performers deserve contract language that protects them from having their identity and talent exploited without consent and pay.”

But not only writers and actors are fighting for their IP. News outlets including the New York Times, CNN, Reuters, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) have recently blocked a tool from OpenAI, limiting the company’s ability to continue accessing their content. A Reuters spokesperson said it regularly reviews its robots.txt and site terms and conditions. “Because intellectual property is the lifeblood of our business, it is imperative that we protect the copyright of our content,” she said. In early August, outlets including Agence France-Presse and Getty Images signed an open letter calling for regulation of AI, including transparency about “the makeup of all training sets used to create AI models” and consent for the use of copyrighted material as the companies behind the AI tools are often tightlipped about the presence of copyrighted material in their datasets.

There is also a push for protection of works created by AI, though. It has been spearheaded by Stephen Thaler, chief executive of neural network firm Imagination Engines. In 2018, he listed an AI system, the Creativity Machine, as the sole creator of an artwork called “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” which was described as “autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine.” The Copyright Office denied the application on the grounds that “the nexus between the human mind and creative expression” is a crucial element of protection. And a federal judge in the US recently upheld these findings that a piece of art created by AI is not open to protection.

Learning and Innovation

On the plus side, AI has the potential to generate vast amounts of creative content quickly and at a relatively low cost. This increased production has the potential to expand the public domain by adding new works that can be freely used, shared, and built upon. Plus, access to a wealth of AI-generated materials can not only enhance learning opportunities but also innovation.

Media and entertainment powerhouse, Banijay just announced the AI Creative Fund, a new opportunity for producers and labels across Banijay’s 21 territories to showcase ideas with technology and innovation at their heart. James Townley, Chief Content Officer, Development at Banijay says “We’re extremely passionate about innovation, and this latest AI Creative Fund will empower our producers across the footprint to create new formats that embrace tech, whether that be central to the show, or redefining the production process. We’re in a new era of technology and innovation, and while human creativity will always prevail, it’s important to work alongside the tools that are available to contribute to the future of ground-breaking entertainment.”

As we have seen, there is an ongoing debate about how to strike a balance between protecting creators’ rights and ensuring broad access to AI-generated knowledge. That’s why the need for new legal frameworks and regulations tailored to AI-generated content is an important topic of discussion. How should copyright laws be adapted to address the unique challenges posed by AI?

According to Danielle Lauren, copyright and IP is such an integral part of the TV industry and it needs to be protected. Creatives deserve financial compensation, especially if their works are profiting AI users. It’s a multi-layered and very complicated area that needs a solution. Firstly we must acknowledge that artistic works have been scraped without permission and that conversations around compensation need to be on the table. Secondly, we have to be able to have the option to choose whether we want our future works to be part of AI model training. Already there are tools we can use to opt out of having our work scraped. Thirdly licensing and royalties. If you’re going to be directly using artists’ works to generate new content, those artists deserve to get paid. This isn’t a case of “inspired by”, this is a computer pulling apart the DNA of an auteur and ultimately using that genetic code to create. Ultimately the human who created it should decide how it can or cannot be used. If your work is famous enough to be used to prompt an AI then you deserve to see a backend.