For content owners and creators, social media platforms have long been viewed as an opportunity to promote shows that are destined for free TV, Pay TV and streaming services. But social platforms are also becoming increasingly significant as content-creation opportunities in their own right, morphing into broadcast platforms as traditional suppliers of content take advantage of the wider – and younger – audiences that social media have to offer.

Trailers, behind the scenes footage, bonus content, conversations with cast and competitions are just a few ways that viewers – especially elusive young audiences – can be directed back towards where the big production investment lies. But social platforms have for some time been offering more than simply marketing opportunities.

Influencers were first to prove the point, illustrating that there was a robust sponsorship/ advertising-driven model for short-form video – if you could get your audience up into the millions. More recently, traditional content creators have also explored the potential of these platforms – testing whether it is possible to produce drama, factual, entertainment and animation shows that can generate ROI in this arena. All of the major social platforms have supported this activity to a greater or less extent – but it’s a fast-moving space where requirements constantly change. So here are a few thoughts on what’s working right now…

TikTok

This is the latest social-media platform to burst on to the scene, quickly joining the likes of Instagram and YouTube as the preferred platforms for young audiences. Its core proposition is short, shareable video – much of which is reminiscent of the content that works on other platforms. Pets doing funny things, people reacting humorously to things they have seen on the internet, opportunities to copy dance moves, challenges, insights into celebrity lifestyle, are some examples.

As of February 2021, TikTok had 100 million active monthly users in Europe and the same again in North America. So not surprisingly it has attracted the attention of traditional content creators which want to leverage the appeal of the platform and repurpose it as a video broadcast platform. In Europe, TikTok’s relationship with media companies is overseen by European Strategy Manager Edward Lindeman, who recently contributed to this talk to the Royal Television Society in the UK.

At its core, Lindeman said, TikTok content needs to be vertical, and not more than 15-30 seconds in length. His key advice is to spend time on the platform, getting to know how it works. Echoing a point made earlier, the main emphasis at the moment seems to be on content that can amplify existing brands. NBC’s Hayu, for example, edits content from TV for use on TikTok. ITV senior digital producer, entertainment, Jen Leeming, in the same RTS session, talked about how ITV used the platform to support the latest series of I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here! By the end of the series, the show had 421,000 followers, 23.5 million video views and four million likes.

Key takeaways from Leeming’s summary were that: ITV used a dedicated producer for TikTok – emphasising the point that not all digital platforms are the same; “funny and gross” content worked well; content needs to have an exclusive feel to it to make it compelling – for example, ITV used the platform to reveal cast members on the show.

There’s no particular evidence that traditional producers are making original unattached content for TikTok – though Lindeman did cite Guinness World Records (top photo) as an interesting early adopter on the platform. Showing clips of zany world-record attempts seems like a no-brainer for TikTok. Other useful reading about TikTok includes this TBI story, where one interviewee notes that putting clips on the service is possible, but that making “a show, its star or broadcaster a part of the conversation would be wiser. You need to think of trends when you think of TikTok – you’re either going to start a trend or join one.” As a final note, Lindeman is seeking to push live functionality and has worked with Sky News on using TikTok as a live broadcast platform.

Twitch

This is predominantly a livestreaming platform for gamers – a place where fans go to watch Fortnite, League of Legends etc being played by their favourite gamers. But the character of Twitch definitely shifted in 2016 when the Amazon-owned platform launched IRL (In Real Life), a streaming category where audiences could go behind the scenes and learn about their favourite gamers when they weren’t playing. IRL quickly gathered momentum and, in 2018, it introduced thematic categories such as Art, Food & Drink, and the innocuously titled Just Chatting – where Twitch users go to talk to charismatic or like-minded strangers and not just gamers. It’s now one of the most popular destinations on the platform, garnering 81 million hours of viewing in 2020.

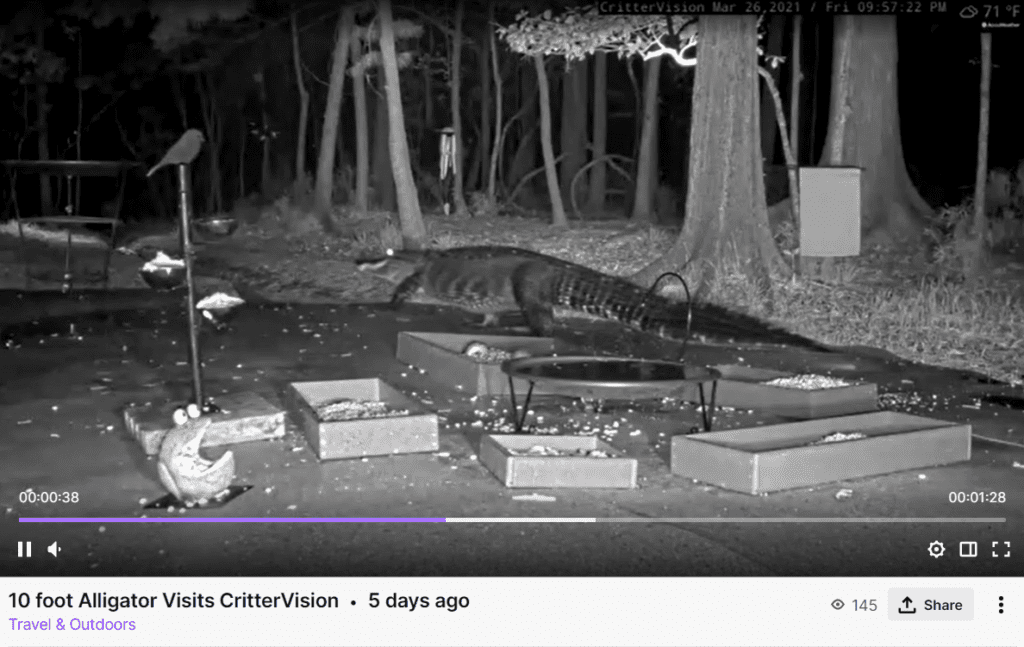

So what exactly is the content creator opportunity here? Well, the emphasis is on like-minded communities connecting in real-time. Technically, there’s nothing to stop a Twitch creator posting tutorials on dating, travel or finance, but the DNA of the platform is live, shared experiences – going on safaris or listening to live music performance. Obvious opportunities include wildlife observation shows, for example CritterVision (above, which is no more than a fixed camera looking out for wild animals in a back yard…), but there have also been successful examples of reality-based gameshows.

Anyone daring to enter Twitch as a potential broadcast platform, needs to think hard about their strategy however – especially brands. Some gamers have embraced the IRL opportunity, seeing it as a way to build a more intimate and authentic relationship with fans. But there is a segment of the audience that is uncomfortable with – and antagonistic to – the emergence on non-gaming content. So content creators need to consider carefully who their target market is and who they might be alienating if they try to leverage Twitch.

YouTube

YouTube is no longer just a platform for influencer and UGC content. On the one hand, it is a powerful way for traditional content owners to promote their brands via trailers, sample episodes, behind the scenes content etc. On the other, it is a significant player in content commissioning via its YouTube Originals activity.

For a while, YouTube seemed to be interested in emulating SVOD platforms like Netflix, commissioning scripted content like Cobra Kai and putting it behind a paywall. But in recent times it has pivoted – so that the emphasis is now on commissioning ad-supported factual content. In 2020, for example, YouTube doubled its original output to around 100 series – mostly documentaries. Coming into 2021, Luke Hyams, head of originals EMEA at YouTube gave a useful insight into the platform’s approach during a Royal Television Society conversation. His key observation was that YouTube commissions are typically shows that “blow up” existing trends on the platform. In other words, Hyams looks at personalities, trends and formats that are gaining momentum and then commissions stories around them.

Hyams cites the example of Terms & Conditions: A UK Drill Story (below), which was commissioned, in part, because of the “staggering” amount of drill music videos being consumed. This documentary is slick and well-produced, but it does carry some hallmarks that are distinctively YouTube – such as the direct interviews to camera and the use of an authentic narrator, Mr Montgomery.

At key points, the narrator invites the audience to comment on his opinions – and we also see him recording content, a stylistic touch that relates back to influencer culture. Another key way of finding out what YouTube is looking for is through its annual Brandcast event. At 2020’s event, for example, we learned that food programming on YouTube had seen a 45% increase in viewership year-on-year. In 2020, YouTube also pledged to create a $100m fund to support black creators on its platform.

This social media platform is primarily known for short-form UGC video content that moves around the platform virally integrating itself into text- and image-based conversations with friends and family. But it made a major move to become a broadcast platform in 2017 with the launch of Facebook Watch. In year one, Watch had a budget of $1bn, rising to $1.4bn in 2020. The platform has had success across genres in terms of critical response, with shows like Sorry For Your Loss, a half-hour drama that ran for two seasons; and The Real World (below) a reality reboot of the iconic MTV show.

In terms of length, the sweet spot for Facebook Watch non-scripted content is around 15 minutes, though it has commissioned everything from five- to 50-minute episodes. But Watch has struggled to build large enough audiences to generate meaningful ROI – which may explain stories last year that is was switching emphasis away from originals towards talk shows and licensing clips from TV networks and sports leagues – both of which would be ways of increasing the volume of content it has on the platform.

The switch towards talk shows has some logic given that one of the platform’s most talked about productions is Red Table Talk; this is probably as good a guide as any for producers seeking to work with Facebook. For producers of original content, it’s worth noting that Facebook Watch is interested in content that is shareable. But the fact that the platform is also licensing clips should be of interest to distributors. Typically, Facebook operates on a revenue-share basis with 55% of accrued revenues going to the content owner.

This platform was acquired by Facebook in 2012, and has since has become one of the preferred platforms for young audiences – so it stands to reason that content creators and brands want to be seen there. The core of the platform is sub-10 second videos but in 2018 Instagram also launched IGTV, a mobile app that allows content creators to upload shows up to 15 minutes in length. In practice, IGTV has come to resemble YouTube, in the sense that it is dominated by channels of content. This tends to favour influencers, brands, thematic destinations and any other organisation in a position to post regular videos updates.

If you check out this link, for example, you’ll get a sense of what works well in the IGTV context. Good examples include Discovery-owned Food Network and BBC News. For producers, the option is to develop a channel that can sustain over an extended period of time – or try and produce into an existing channel. Who knows, maybe you could approach NASA and suggest some content strand that works within their channel? As for format, content should be short-form, shareable, probably vertical (but not necessarily) and in touch with a youth sensibility. Browse the Food Network and you’ll see a strong emphasis on bright colours and diverse presenter-led content.

Snapchat

This platform’s growth has slowed in recent years, but the youth-oriented mobile app still has more than 200 million daily active users – so it remains a force to be reckoned with. Like Instagram and TikTok, Snapchat’s primary currency is super shortform shareable video – but the platform has also made a concerted drive into the professional content space via its Discover Tab. Here, audiences can find Snap Originals (new shows made by Snap) and content provided by partners such as Discovery, Viacom, the US networks and sports channels.

The latter can either be cut down versions of original shows or bespoke content created for the platform. According to Vulture, there were around 95 Snap Originals by 2020 with drama Endless the most successful of them all with 38 million viewers. News, drama, comedy, reality and entertainment have all featured at some point in the platform’s evolution.

The optimum length for a snapshot show is five minutes with eight minutes regarded as the maximum that works. Shows need to grab audience attention immediately, are shot vertically and need to be edited tightly. Vertical shooting means scenes tend to focus on very few people – with split screen preferred over trying to squeeze two people in next to each other. The Vulture article referred to above provides a lot more detail about the grammar of producing for Snapchat. Broadcasters that have embraced Snapchat include Channel 4 in the UK, which has re-cut shows including First Dates Hotel, Celebs Go Dating and Hollyoaks (above) for the platform. To date, C4 has tended to focus primarily on repurposing TV content rather than making originals.

This social media platform has been used by the TV industry for the last decade, primarily as a marketing tool for engaging with fans and building conversations arounds shows. We recently cited Netflix’s Twitter strategy for Shonda Rhimes’ Bridgerton as one reason why the show blew up so dramatically over the Christmas period. In 2015, the company was one of the first to embrace the live streaming trend with the launch of its Periscope app. Periscope is now seen as surplus to requirements but that doesn’t mean Twitter has is ignoring its potential as a live video streaming platform.

As TechCrunch notes, “Twitter has been doubling down on video services within its app, building out Twitter Live and recently launching Fleets so that users can share moving media alongside their pithy 280-character observations, links and still photos.”

Twitter remains a complementary platform – best used to amplify content on other platforms – broadcast platforms for example – rather than as a destination in its own right. However some content creators have spotted an opportunity to use its functionality in gameshow-style content. TV Asahi, for example, has a format based on the playground game Tag (aka ‘It’). Here, people are chased around in the open wearing a sign on their back that invites members of the public to reveal their location to the chaser via Twitter.

One interesting point to note about Twitter is that it acquired short-form video platform Vine in 2012 – and then closed it in 2017, citing competition from the likes of Snapchat and Instagram. Ironically, it did this just as Chinese short-form video platform TikTok was launching – and look how that has worked out. There are good reasons why Vine failed, but Twitter execs must have some regrets about the decision to vacate the short-form video market.