From headsets like Oculus Rift, HTC Vive and PlayStation VR to a stream of inventive narrative projects, virtual reality was a prominent topic at MIPCOM 2016, with a raft of sessions exploring its creative potential, and some of its business challenges.

The discussion kicked off on Monday with a session on how creatives are trying to weave narratives in VR. The panel of Discovery Communications SVP of development and operations Nathan Brown; Secret Location president and executive producer James Milward; and Sky VR Studios / Sky Cinema executive producer Neil Graham related their experiences.

“Why is the story going to be meaningful in this format?” is the key question, according to Milward. “We decided that if we were going to tell a story that had a VR aspect as part of it, we wanted to lean in to VR as part of the narrative,” he said of Secret Location’s VR project Halcyon. “The show is a procedural… then the VR is the crime scene of the murder.” It’s fully interactive too: viewers can move around and gather evidence, before watching how the show’s characters solved the crime.

Brown talked about Discovery’s work in VR. “With VR we’re able to bring these exotic places around the world that people couldn’t otherwise visit… to them through their headsets… It truly has that profound effect of having presence in a place.”

The panel talked about the lexicon and grammar of virtual reality, and the idea of creating a new cinematic language. “If you’re filming in real-time, the point about proximity is key,” said Graham. “What we’ve been talking about is finding subjects where presence is central to the experience, and really thinking about how you’re viewing it and why you’re viewing it. Whether you’re a passive observer… or you’re interacting with the content.”

Milward talked of it as a spectrum. “At one end of the spectrum you have the closest to linear, which is just taking a camera and shooting 360 degrees. The audience doesn’t have the chance to participate other than where they look,” he said.

“As much as there is the other end of the spectrum, there’s a lot of use cases and really excellent executions that we can do with 360 and 360 3D video… giving you that sense of presence and that ability to be somewhere where you wouldn’t be able to be, or wouldn’t want to be.” An Ebola hospital, as an example of the latter case.

But at the other end of the spectrum is more game-like: “Real-time rendered, things happen in response to what you’re doing,” he said. “There aren’t really any good examples today of truly interactive narrative happening other than in hardcore console gaming that is being ported over.” Milward said that the adoption of Sony’s PlayStation VR will determine the success of this.

Are the likes of Discovery and Sky commissioning VR content from producers? Brown said that “we just started making VR. We had an opportunity, we had an ambition to really push storytelling and technology: we didn’t sit around and wait for a strategy… we just started making things… we’ve made bad VR, we’ve made good VR. We’re making more good than bad.”

Discovery “is not arrogant or ignorant to think we can do everything better than everyone else” so it’s looking for partnerships around VR to continue pushing the boundaries. It’s also looking for brand partners to sponsor its content, as the most likely content-funding model. “You’ll start to see transactional, T-VOD will start to take place, and you’ll see subscription models as well. We’re pursuing all of the above.”

Are certain genres suited to VR? “Sports and arts are really suited to VR. Music too,” he said, of a commission with the English National Ballet to film their new performance of Giselle in VR. Sky worked with producer Factory42 to work out how to shoot a VR experience for a ballet, taking one of the segments off the stage and into a factory location. Sky is exploring drama too though: a project called Britannia that includes shooting in the centre of Stonehenge.

“A lot of bad VR has been shot where the VR camera has been put out of the way of the traditional cameras, and that doesn’t work because you’re not close enough to the action… if VR is just a sidebar to a traditional production, it’s not going to work.”

Milward talked about using a transactional model for VR with Halcyon, while adopting a flexible approach to licensing its content to distribution partners. “For us the model was to try something new… just hack away at the financing until we could get something built,” he said.

Is VR here to stay? “A lot of eople have compared i tto 3D but it’d completely different. 3D was a layer over a n existin model, but VR is not just a new eperience: it’s a new ecosystem.”

“I think it’s here to stay,” agreed Milward. “And we’re not looking at VR as a silo… for us VR lives in augmented reality and mixed reality, and the ability to expand how we view content and space and immersion… VR will continue to evolve and change.”

In other words, the things producers can learn from making VR content now may well be applicable to other formats and mediums in the future. “It’s definitely here to stay. There’s too much investment in the space, especially as you see the different platforms proliferate,” said Brown. “It’s a great time to be a VR content maker. Content is the oxygen that fuels all these different platforms.”

Another session discussed the spectrum ranging from audiovisual content to gaming – or, indeed, the collision between them. Arnaud Colinart of Ex Nihilo / Agat Films and Amaury La Burthe of AudioGaming talked about their work on feature film and VR experience Notes on Blindness, based on the audio diaries of writer John Hull, whose sight deteriorated over decades until he was completely blind. MIPBlog’s own Angela Natividad moderated.

The project was based on more than 16 hours of audio content from Hull, with Ex Nihilo and AudioGaming having already worked together on Type:Rider, a game about the history of typography. Notes on Blindness started as a series of podcasts using the audio diaries, before evolving into a VR experience.

« We really started from the audio material and the story John wanted to tell. We used the tape sand he transcription and we tried to tell a story. We isolated several moments in the tapes… and we tried to elaborate interactive situations, » said La Burthe. « We started to experiment a bit, but we realised that by doing something that was only audio-based we were losing a lot of people: we were losing the sighted audience. » So the team started to work on visuals that aimed to give a sense of what it’s like to be blind: objects can only be « seen » if they are emitting sound in Notes on Blindness.

At this point it was an interactive audiovisual project, but at some point the idea of making it a virtual reality narrative cropped up. « Depending on how much you look around, the story’s going to be slower… if you look a lot around we’re going to trigger a few additional things, » he explained. Like video games, the experience tries to tread a line between being too simple, and thus boring, and too complex, and thus anxiety-inducing.

Colinart said the project was « clearly a niche », but the makers applied to a selection of festivals around their world, to get it in front of the tech and artistic communities. « There is few content available. Working on VR content right now, especially if you have some selling point: art direction or concept that didn’t exist until now, you can really bring attention to your project. » The film was also showcased on the content homepage of the Samsung Gear VR headset after being spotted by Oculus VR. « You really need the push of a tech company, » he said, alongside a marketing team on social media.

How was the project financed? Colinart said that it was easier for a broadcaster like ARTE to invest in this kind of project if it’s linked to a linear format. « It’s close to the structure of a feature film, » he added, with funding coming from a variety of sources. La Burthe talked about the need for supportive backers, especially in this case, where what was originally an audio-only project ended up as a fully-fledged VR experience.

Was there ever a moment where one of the partners worried about that final product? « Um, yeah. We had some very stressful moments, especially on the tech side. The ecosystem of tech is changing a lot » said Colinart. La Burche continued, talking about the iOS version of the app. « 48 hours before the release, we discovered that the new version of iOS 10 introduced a major bug… all the people in the screenshot were replaced by a white dot! It was a long 48 hours… You don’t have technical problems like that on an animated series. You’re not going to lose all your rendering 48 hours before showing it to the public! » The responses were worth it: « Some people cried after the first four chapters, » said Colinart. « We were happy to see some people crying because that’s where we wanted to go… to have this emotional connection, » agreed La Burche.

Why should broadcasters greenlight this kind of project? Colinart talked about his 20-year relationship with ARTE, and the trust in that track record. « They greenlight a project because in a way we replied to the question ‘why a VR project?’. Because it was relevant to immersion… you will discover a new perception of the world. »

Colinart talked about the « fail-fast culture » of his company. « The culture of TV, especially in Europe, we don’t have this culture of failure. We need to succeed. And the success of studios such as Pixar and big video games studios is based on the possibility to fail and learn from these mistakes. It’s impossible to start these kinds of projects if you are not ready to fail… and learn from your mistakes, and restart. »

On Tuesday, a panel session focused on the journey from passive viewing to virtual interaction. It featured Hervé Fontaine, VP of virtual reality B2B and business development at HTC; Emilie Joly, CEO of Apelab; and Wilfried Van Baelen, CEO of Auro Technologies. Orange‘s VP of digital content and head of VR Morgan Bouchet moderated.

On Tuesday, a panel session focused on the journey from passive viewing to virtual interaction. It featured Hervé Fontaine, VP of virtual reality B2B and business development at HTC; Emilie Joly, CEO of Apelab; and Wilfried Van Baelen, CEO of Auro Technologies. Orange‘s VP of digital content and head of VR Morgan Bouchet moderated.

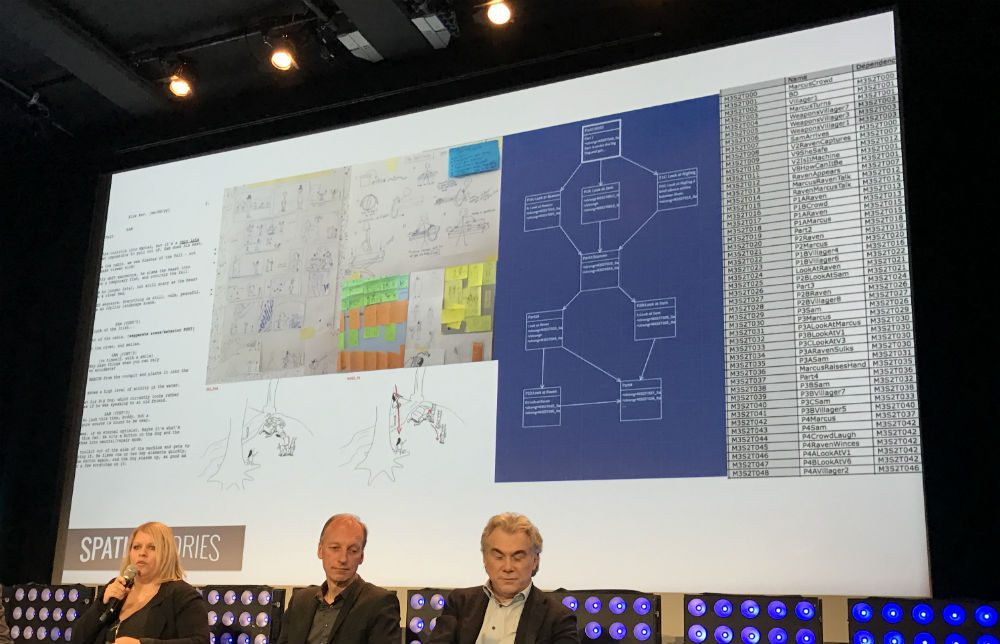

Joly talked about her company’s Spatial Stories project « mixing workflow from video games and film together, which is kind of a hard thing to do ». It’s a series of original content, but also a set of tools and a framework for creating VR. She added that in Spatial Stories, « the user is the camera… and he usually never does what you want! So your goal as a storyteller or a designer is to build a world in which he will be able to interact: what I call organic narrative. »

Joly showed off an example of what a virtual reality « script » looks like too:

HTC’s Fontaine talked about how VR started from gaming. « I think it’s clear for everybody that the potential for VR is far broader than gaming, » he said. HTC has just launched its Viveport app store for non-gaming content for its Vive VR headset.

Fontaine said that while traditional films have offered the promise of taking us somewhere else without actually being able to deliver it: « Virtual reality is now getting us to a time when it is going to be possible, » he said. He praised The Apollo 11 VR Experience app as one good example. « You become the pilot who’s going to land the module on the Moon. If you don’t rush it! »

« We had a PC, then the web came and it really revolutionised the way we could access and deal with information. Then touchscreens came… but we feel that virtual reality is an even bigger step. It completely fools your brain: you suddenly feel you’re somewhere else. And that creates emotions… When you have a flat screen, you can’t really feel emotion. »

Fontaine highlighted social, shopping and other potential VR experiences. « If you think about education for example, the potential is huge… VR has that possibility to multiply the amount of time you learn through experience rather than learn through listening. » He added that creativity and design will change: for example, sketching in 3D in the virtual environment around you.

Van Baelen talked about how audio technology has evolved, from mono to stereo, then 2D surround, and 3D surround – « surround sound with height » – and he claimed that « the more we hear, the more we can feel ». He said that more evolution will be required to provide the best experience for VR.

« VR is its own medium and we should definitely look at it almost as a blank slate, and get inspired by architecture, film, games, everything around it. And explore what it is, and what interactivity is at the same time, » said Joly. « It’s really its own, and there’s a lot to rethink and to think about now. »

« George Lucas once said that VR is at least 50% of the experience in a movie. In VR I think it’s more, » said Van Baelen. « It’s 80% at least! » replied Joly. She also talked about how Apelab uses game engines to produce its content, but also working on scriptwriting technology that is connected to the engine, to make writing and prototyping easier. « It’s very difficult for them to create in a linear way, so you need the interactive bit inside the tools. »

On Wednesday, meanwhile, a panel got real about VR, asking « where is the money? » for the creative projects that MIPCOM attendees have been planning. The panelists were Anthony Geffen, CEO and executive producer at Atlantic Productions; Kay Meseberg, head of VR / 360 at ARTE; and Secret Location‘s James Milward again. The moderator was Oliver Autumn, managing partner at AutumnCourage Film & Events.

On Wednesday, meanwhile, a panel got real about VR, asking « where is the money? » for the creative projects that MIPCOM attendees have been planning. The panelists were Anthony Geffen, CEO and executive producer at Atlantic Productions; Kay Meseberg, head of VR / 360 at ARTE; and Secret Location‘s James Milward again. The moderator was Oliver Autumn, managing partner at AutumnCourage Film & Events.

Geffen kicked off, talking about working in factual VR productions and installations for museums, through Atlantic’s Alchemy subsidiary. « A lot of it was R&D for a long time. Our first path to monetisation was to set up relationships with museums around the world, » he said. « These are proper films, about 25 minutes in length. » And it gets around the concern about people not owning VR headsets: the museum has them at the installation for visitors to use. The business model is usually ticketing. « There could be a bigger market in it. I thought it was gong to come and go, but now I think there’s a definite place for that content inside institutions. »

Milward talked about Secret Location’s work in VR in the last three years, including making a VR experience for Fox’s Sleepy Hollow show. « The only way to get it in front of anybody at that point was to do it as an installation, » he remembered. Audiences weren’t paying to enter: these were free experiences to promote a film or TV show. But now Secret Location is trying similar distribution models in China around « VR arcades » – an evolution of internet and gaming cafes, with VR headsets in situ.

« It’s my opinion that shortform marketing executions don’t have a big audience. I think that of people may try it… but it’s not the thing that sustains the ecosystem or sustains or builds an audience around a platform, » warned Milward. « These are fun, casual experiences, but these are not ultimately where the money’s going to be. »

Meseberg talked about the potential for 360-degree video, moving step-by-step into VR, and his desire to take ARTE viewers along that path. It has created installations for festivals and other locations too. The company works with specialist VR studios. « We try to publish content which is more or less 80% related to broadcast programmes, » he said: so VR elements as spin-offs from shows that are on the air.

« The technology to create that is getting more accessible, » he continued: from shooting to editing and adding interactive elements. « It’s always the story. The production companies we work with, they always know what a good story is. And based on that we think about is it something to do in 360, is it something in VR, or is it [just]a broadcast programme? »