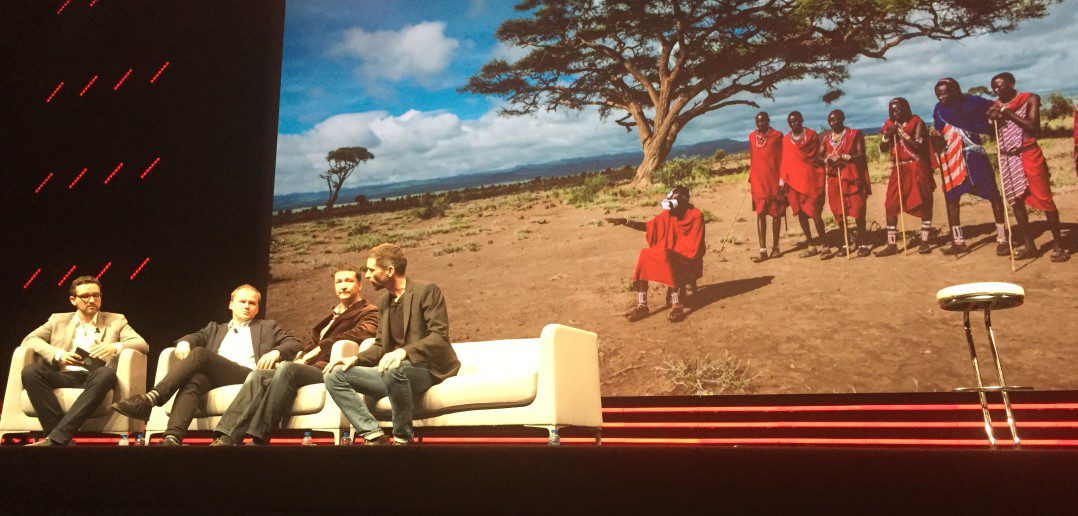

Above: managing director Matthias Puschmann of VAST MEDIA, Kay Meseberg, head of 360/VR at Arte; Thomas Wallner, president and co-founder of Deep Inc.; and Stéphane Rituit, co-founder of Felix & Paul Studios.

This lengthy and exciting session, led by managing director Matthias Puschmann of VAST MEDIA, began with a general survey of virtual reality—what it includes, current hardware players and creative options. With help from panelists later in the day, we also learned how storytellers can begin to build a vocabulary for this new world, and what rich opportunities lie in wait.

« VR is a concept, » Puschmann began. « the concept of getting rid of technical boundaries and placing the viewer in an experience. It’s all about immersion. But how do you tell stories where viewers have freedom to look around? »

File this question in your brain bin, because we’ll come back to it later. Quickly though, a survey on VR’s development up to this point. There are three different types of VR currently:

- VR worlds: 3D renderings used mostly in gaming, which, as Puschmann points out, « has a long tradition of creating interactive experiences for players. VR and gaming are very interlinked. »

- Cinematic VR

- 360° videos—content created with real cameras, and amenable to storytelling. « These are simply flat videos morphed into a sphere for playback, » said Puschmann. « Most are monoscopic; it’s harder to produce 3D stereoscopic videos, where two videos are mapped together to provide depth in the experience. » Google added 360° support to YouTube last year.

For your storytelling purposes, we’ll mainly go over the last two, because they’re most relevant to the industry. Onto the hardware—one of which is already out, and the rest of which are slated for launch this year:

- Google Cardboard: For €15, you can turn your smartphone into a VR headset. Supported apps in the Google Play app store have seen 25m downloads in the past two years. Many of them are games or branded experiences. (This take on VR is so dirt-cheap and easy to produce that McDonald’s Sweden just produced its own Cardboard VR offering… out of Happy Meal boxes.)

- Samsung Gear VR, an affordable premium mobile VR offering that, somewhat like Cardboard, turns your Samsung smartphone into a VR headset. Oculus is providing content for it.

- Oculus Rift. Its Kickstarter campaign from 2012 hit 10 times its pledged goal ($2.4m from an ask of $250k). Facebook purchased the company in 2014 for a whopping $2bn.

- HTC Vive, a high-end device with room-scale technology. « For €900, it provides high quality images, » said Puschmann; it is €200 more expensive than Oculus, and comes with controllers and base stations that track your movements in a room with precision of less than 1mm. « To take advantage, you need to have room around you to set up that tracking technology, » Puschmann added.

- Sony PlayStation VR, designed to work with PlayStation (which has a very large subscriber base). « Sony calls it the social screen that allows gamers to watch others play in virtual devices, » said Puschmann. Sony is already working on producing 160 accompanying VR experiences for it.

Google is also expected to announce a new device, most likely at the IO Developers Conference in two months.

Onto the possible use cases for VR:

- The future of gaming. « There are virtual reality theme parks where you can fully immerse yourself in VR, » where effects like wind make those virtual worlds feel more convincing, in addition to « large spaces consisting of rooms, mapped within headsets, » said Puschmann. Imagine the implications for multi-player gaming or even learning.

- Augmented live experiences. « Attend events and visit locations remotely, giving fans a way to experience new artists, standing onstage, going backstage or experiencing rehearsals. » The NBA and NFL are already producing VR content, not to mention the travel sector: « Ways to experience remote locations within a headset. »

- The adult industry, which has always been a trailblazer for new technology. « Per MarketWatch, the VR adult content sector will be worth $1bn in next ten years, » said Puschmann.

Then there’s the TV industry, which deserves its own category. While experiments so far remain too few to be mainstream, there are enough that you can start learning from mistakes and successes. « Numerous companies are working on content, » said Puschmann. « Many broadcasters also developing new experiences for viewers; some original, some extensions of existing shows and formats. »

Discovery VR is a broadcaster platform for immersive 360° videos, mostly based on its on-air formats, or digital shows.

Sky News in 360°, designed for Facebook and Oculus. « This year they’re producing over 20 experiences across news, entertainment and other genres, including Formula 1, » said Puschmann. Their 360° Migrant Crisis report provides a four-minute, first-person experience of the European migrant crisis. It was made in collaboration with Jaunt, a virtual reality app and production firm into which Sky, ProSieben and other partners have invested over $100m dollars so far:

MSNBC Lockup 360: A 90-minute expeirence that immerses you into a maximum security prison.

BBC’s 360° Virtual Voice: A virtual audition walk and coaching sessions for The Voice, in 360°, « a fun way for fans of the Voice to experience what it’s like to be a contestant on the actual show. » The BBC’s also looking at cooking and horrror genres.

D8’s Nouvelle Star: This experience includes livestreaming with voting in VR; users can vote by looking up and selecting the candidate with their eyes. It is broadcast to Cardboard and Gear devices.

ABC’s Quantico – The Takedown VR, marking The network’s first scripted VR experience and sponsored by Lexus. Slide into the role of a new FBI recruit; in-video easter eggs add to the series storyline.

« We’ll soon be seeing more spherical content on YouTube » as equipment gets less expensive, said Puschmann. And as device prices decline, market penetration will grow.

But back to our original question: how do you tell a story in a medium without a defined vocabulary, and in a setting where users can look anywhere they want?

Let’s hear from our panelists.

First up: Kay Meseberg, head of 360/VR at ARTE360.

For the content ARTE360 produces, « We don’t reinvent the wheel, we won’t do something that ARTE isn’t known for, » said Meseberg. The strategy is to create VR and 360° experiences based on topics ARTE’s team already knows very well, which makes the investment less risky. Mostly you’ll see documentary, fiction, journalism, performing arts, concerts, and experimental interactive publications.

ARTE’s first-ever VR fiction, I, Philip, is about science fiction author Philip K. Dick.

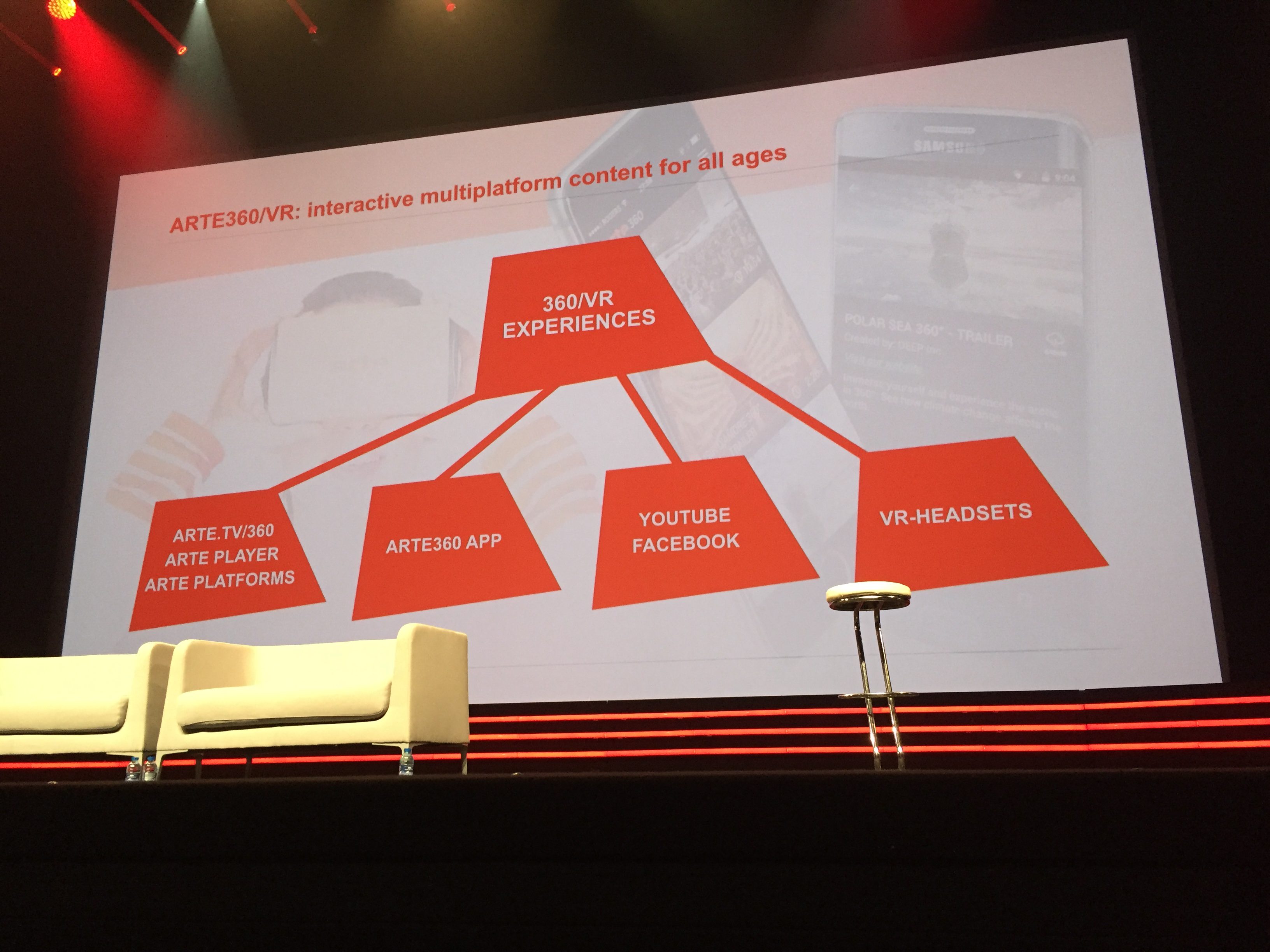

Here is a chart that highlights ARTE360’s distribution model:

« These four different parts to distribute the content are interesting, » said Meseberg. « Like every broadcaster, we have an audience that is old. But on the web, you have an audience around 40-45 years old; for mobile it’s the same, on social they’re around 35 years old. For app-mounted VR headsets, we don’t know, because it’s really new. »

ARTE also commissioned The Edge of Space in partnership with Deep Inc. Thomas Wallner approached the stage to talk more about that collaboration.

« I want to talk about the challenge of making a film in 360° where the viewer has the ability to look around, » said Wallner. In the case of The Edge of Space, a 12-minute narrative film, the challenge was to ensure that users don’t drift off and fixate on something that takes them off the path of the tale.

« We invented a piece of VR vocabulary: Forced perspective. This gives you control as a filmmaker to show the audience what they’re supposed to see, based on where they’re looking. This is very important for narrative. »

ARTE captures the gazes of people as they watch every four seconds. « We have collected 28m gaze points to analyse, » and 1,2m for Edge of Space alone, said Wallner, adding that they can be rendered in real time. In the image below, red is where people focus the most; green is the next-most, and blue is the falling-off point:

The key is to keep the action happening where people are most likely to focus. « We’ve been doing this for years. It’s so effective and seamless no one knows what we’re doing. So the viewer doesn’t feel affected or manipulated; they just see what we need them to see, » said Wallner.

Other elements of forced perspective come into play for things as simple as deciding what to do with the title. What if it’s behind you because you turned around?

Using Deep Inc.’s Liquid Cinema technology, any film element can react to the gaze of a viewer… so the title can actually follow where you’re looking, ensuring you’re seeing it.

But you can’t move everything for the distracted gaze, which brings us to our last Deep Inc. trick: How do you get heads to turn back to the action? The solution is laughably simple: Just begin darkening the screen to the left of the user’s gaze; they’ll naturally start to drift toward the brighter imagery on the right. « We all naturally follow the light, » said Wallner.

Asked how « guided » the user experience should be, Wallner was honest: « As one of the leading experts, I have no answer. I can only say we’re all experimenting with this. On the one hand you have pure experience with no story, and on the other side you have a very strong story. Sometimes when there’s too much story it destroys the experience, and when there isn’t enough story, there isn’t enough context. Everyone has to decide what to be in that continuum. There are no rules; they’re being written now. »

But this should motivate, and not detract, creators.

« We should not be held back by the fact that the medium isn’t perfect yet, » Wallner said. « Perfection is great, but we have everything in our hands to explore the medium from a storytelling point of view. When, years down the line, the resolution is better and everything is stereoscopic and holographic and I don’t know what, we’ll still need the vocabulary that we invent today. »

He turned back to the audience before concluding his presentation. « You know how to tell a story, and you’re really good at it. I believe that technology has to be invisible; it’s about the experience. If I want to be a painter, I need a brush, and in this medium there is no brush. »

So Deep Inc. invented one: Liquid Cinema, which he hopes content creators will pick up. « I call it Liquid Cinema because it’s all about the flow of narrative, » said Wallner. « I invite you to work with it, because it’s for you. »

He added, « This medium shouldn’t be defined by technicians but by storytellers. By working with it, you will define the vocabulary for this medium. Join us in creating the language of tomorrow. »

Next up, to build on what we can do with this « language of tomorrow, » was producer and co-founder Stéphane Rituit of Felix & Paul Studios in Montréal.

He began by describing the complexity of a true VR experience. « We had to invent the pipeline for this kind of content creation, and data management, because it’s a huge amount of data, » he said. « To give you an idea, the resolution is a sphere of 10k per eye. Then we have to develop applications to distribute the content. »

Sounds like a lot of work. But once you have the tools, you need to work out the storytelling language. Rituit’s system is simple: He asks, « What is the role of the person in this story? » VR is primarily defined by its ability to immerse, so you cannot treat the viewer as a mere audience member.

A few examples from Felix & Paul:

Wild the Experience (Fox Searchlight). « You’re standing alone in the forest. The character Reese Witherspoon is walking beside you, » said Rituit. « Then you hear a voice and turn; behind you, another character is there. Because in VR we know where you’re looking, we can play with transitions everywhere you’re not looking. This creates multi-layer stories, and opens the door do non-linear storytelling. »

Then there’s Jurassic World Apatosaurus (Universal Studios/Oculus). For this, Felix & Paul worked with Industrial Light and Magic to build the experience around you: A park ranger sitting on a piece of wood in a calm, peaceful space.

They’re currently also co-producing different experiences with Cirque de Soleil, including Zarkana, Inside the Box of Kurios, and several others.

« Instead of filming a show and putting you in a seat with the public, we worked with Cirque de Soleil to create new content, » said Rituit. « We take each show, deconstruct it and rebuild from scratch in VR. We give you a reason to be there, to be onstage and part of the show. It has a more powerful impact than being part of the audience. »

Another project is Nomads, which takes place in three parts: Herders, Maasai, and Sea Gypsies, and was an official Sundance Film Festival selection. The first installment follows a yak-herding family in Mongolia; in the second, you’re among the Maasai in Kenya; and in the third, you’re among the sea gypsies in Borneo.

« You have the sense of belonging to whatever location you are in, » said Rituit. « Everytime we explore a project, we ask, what is your role here? What is my reason for being here? In each production, we decide that you are part of the family. »

Lastly, we had the VR Experience with Orange content showcase, hosted by Guillaume Lacroix, senior VP of TV & video partnerships & services at Orange, and Morgan Bouchet, VP of digital content & innovation, and head of VR at Orange.

« The fun thing about VR is if you have tried it, you will immediately know what we’re talking about… it’s so self-easy to understand, » said Lacroix, adding that Orange is excited about the potential from a telco’s perspective. « VR will require maybe two or three times more bandwidth than conventional video, because you have to broadcast images that are behind your back… We view VR as really the next frontier to us. »

He admitted that Orange, like everybody else, does not know exactly what the VR market will look like – which platforms will be most popular, and what kind of content will succeed best – but that « all the actors in the value chain will see their activities changed ».

« We decided to make VR a significant innovation priority for us, » he continued. « In 2016, what we are going to do is one step further. We will actually put in front of our customers a service that will allow them to experience a live service. » Announced last March, it will provide Orange’s premium pay-TV channel OCS in France to people within a virtual environment: a 3D living room with its own TV to watch HD content on, and the ability to choose different skins for the environment. It launches in the third quarter of 2016.

« Obviously this is a first step, and we will include three-dimensional VR content as we go along. We are currently working on a version for PlayStation VR, » said Lacroix. « This will be one additional way offered to our customers to watch OCS… This is our first step into VR. This is a real new media, and we have to learn how to use it. This first experience allows us to understand what it takes to make a great experience. » Later, he added that some areas remain to be settled. « We are still working on the monetisation of these contents, » said Lacroix.

How does he think Hollywood will embrace VR? « It will probably evolve a long time. For the time being we see a lot of entrances from studios or producers to create VR contents around their franchises or around their films as a way of promotion, » he said. « We see broadcasters working on formats that will reflect what they have on their main broadcasts, again to create engagement from the customers. We would like to think we can do a VOD service around that… We have to wait a little bit for more content to be online, and also probably a better way to aggregate those contents so that we have a significant volume. »

Another genre where VR is making waves is documentaries. A panel at MIPDoc this weekend also explored its potential on that front.

Another genre where VR is making waves is documentaries. A panel at MIPDoc this weekend also explored its potential on that front.

Moderated by TBI Vision’s deputy editor Jesse Whittock, the panel included Atlantic Productions CEO and creative director Anthony Geffen; Deep’s Thomas Wallner; and ARTE Germany CEO Wolfgang Bergmann.

Wallner talked about The Polar Sea – a 10-part series about the Northwest Passage – and why experimentation was essential. “From a narrative view point, there wasn’t an example you could copy or rip off. You had to invent it yourself!” he said.

Bergmann explained why he’s excited about VR, from the same project. “We approached this idea from a truly analogue point of view. We wanted to create a traditional documentary, we wanted to involve artists. Global warming is in every mouth, but nobody knows what it means. The only way you can know is to go up there… so how can we find a language and an experience to involve more people?”

The project lasted for two years, with a eureka moment when Wallner realised that 360-degree video and VR could bring something powerful to the project. “I felt like the last apache on a horse seeing a train running fast! It was not only this ‘Oh my god’ feeling, but I immediately understood this is something new,” he said. “So we started thinking, talking: what’s after the oh-my-god feeling?”

“We’re dealing with a new medium, but we’re actually dealing with an old dream, because if you look at the writings in the early history of cinema when people first started seeing images, they started to dream about what the future of the cinema would be like… they actually described the holodeck, 360, 3D, all around you,” said Wallner.

“We’ve now entered that time where through the technology of VR and filming in new kinds of ways, we’re approaching the possibility of fulfilling that dream, except we don’t really know how yet.”

How do the producers approach the task of storytelling in VR? “You just throw everything you know about storytelling out the window, basically, and start again,” said Geffen. “We have 5% of the language of how we should be making these virtual reality films with us right now, and maybe even less. It’s different than cinema, it’s different than television, and it’s extremely exciting when you get it right.”

“We are in the beginning of the beginning of something, it’s page one or two of probably a very big book. My fear at the moment is the hype and the technical development and the high investment will speed up the whole thing so that it overheats… We are at a stage when we should have time to think. Time to experiment. Time to learn to move in this new space. And time also to think about why are we doing this? What’s the reason? Is there any reason, any purpose to go further on with the VR? » said Bergmann.

« My answer is in the moment, what I can see there is extremely interesting first proofs of stuff you can make. It’s obviously the wow thing that you can almost be somewhere where you could never be physically… But in terms of narrating, we are just on our very first steps to understand what is possible. And this is a huge perspective of VR. It’s not less, in my view, than the merger of theatre and film and performing arts.”

Geffen admitted that a lot of broadcasters are wary of VR because they don’t know where it’s going to lead, as well as because of the technical complexities involved in producing great content. “Broadcasters should support it. It’s a good complement to what they’re already doing, and it stimulates storytelling. And anything that stimulates storytelling helps television in my view.”

Wallner said that broadcasters can bring their storytelling chops. “As a broadcaster, you can now broadcast space and time. Before, you could only broadcast a film that was about space and time. Now you can broadcast the moment.”

What we need are proper films,” added Geffen. “In America, everyone’s making the two-minute, the one-minute, but what we need to get this alive are longer stories… The audience want a proper story in this medium. It’s fun to watch yourself jumping off the Grand Canyon or something, but we’ve got the opportunity here to do proper storytelling.”

Geffen worried that VR will be the next 3D TV in terms of hype. “The real worry about VR is it’ll follow the 3D curve… suddenly by October we’ll be sitting here saying ‘what happened to VR?’ because there weren’t enough good experiences,” he continued.

Bergmann pointed out that people won’t wear headsets from morning to night. “Why are we doing this? Is there any reason other than that it’s the next big thing, or the next cool? What is it good for?”

Wallner gave a storyteller’s opinion. “You don’t actually need VR to tell a good story: you can use a shadow—puppet on the wall and move people if the story is really good,” he said. But he believes that VR can also move people, which is why it’s worth exploring.

Who is commissioning VR wondered one producer in the audience. “The broadcasters if they do it are probably adding it on as a little extra, and very little money in that. There’s some advertising money but that probably takes you in the wrong direction. There’s some manufacturing but the manufacturers have been appalling, as with 3D, about putting money in to content,” said Geffen.

“It’s a really big problem, and then if you go out and start shooting it yourselves, if it’s not shot in the right way and in the right format, it’s useless.”