This morning kicked off with a handful of digital panels, brought to you by the Bell Fund. The first of these sessions was The Power of Fans.

Introduced by Catherine Warren, board member and president of FanTrust, this session covered the primal force that is fan culture. We can’t control them, but we can learn to work with and create alongside them. Whether you’re a TV network, platform, studio or talent, fans will be your biggest advocates, keep you honest and push you to new heights.

Or they can tank you in your sleep.

Joining moderator Laurent Colombani, a partner at Bain & Company (far left), speakers for this first digital talk of the morning included founder Ahmed Abbas of DigiSay, Steven Ekstract, group publisher at License! Global Magazine; managing director Kat Hebden of Shotglass Media (owned by FremantleMedia); and CEO Sam Rogoway of Victorious.

One of the interesting aspects of being fan-focused is that, by talking about their own manifestos, each panelist ended up making a big point about the culture they’re trying to connect with. In the case of Shotglass, for example, Hebden said, « For us, it’s about creating digital communities around passion points. »

This notions of passion and community returned again and again, but perhaps was most deeply felt when DigiSay’s Abbas talked about Middle Eastern fans.

« To understand the fans of the Middle East, you need a good understanding of the people, » he said. « Something interesting happened to them during the Arab Spring: They got enlightened. They feel more independent and are relying more on themselves. It’s a duty to express yourself and not a privilege anymore. »

The Middle East’s audience is quite young, so their avenues of social expression include social media, media products and brands. « It’s interesting what people can do on social media with their fingertips. They can force a major TV network to bring down a show from a famous singer because she humiliated some of the fans, » said Abbas, referring to a reality TV show where a star, asked to choose her « best friend » among fans, ended up embarrassing many of them—which alienated the people who identified with these characters.

Being able to identify with what you’re consuming is also critical for building fanbases. « PewDiePie is just a normal guy who did this out of his bedroom, » Abbas observed. « Bassam Youssef »—a contagious star dubbed Egypt’s Jon Stewart— »also started out of his bedroom. So fans think, hey, I can become that person. It’s a different relationship than if you’re a fan of Michael Jackson or someone else you can’t imagine being like. »

Despite super-high social media activity, and highly prolific fictional content production around Ramadan, the Middle East is one of the least exploited countries in terms of content. « People in the Middle East are hungry for good content, » Abbas emphasised. « There’s a big gap between content consumed and produced; people consume about 2,5 times more than is available. If you listen carefully and give them what they want, they’ll be superfans and love you. If you don’t, they will hate you. Beware their wrath. »

Riffing off superfans, Rogoway’s Victorious platform focuses exclusively on this especially passionate segment., representing 500 million fans worldwide. « We were the only company in the world last year to publish 15 of the top 50 apps in the App Store, because we’re the only ones who cater directly to superfans, » he said.

There’s pragmatism behind this model, too: Namely, well-activated superfans end up working for you. « Think of engagement like a rubber band. How do you stretch that rubber band out, knowing you can’t create unlimited content? » Rogoway asked. The answer: You make fans creators.

Hebden agreed, observing that, on Shotglass’s football network channel, they’ve seen a massive rise in fans taking part in the action. « Increasingly they don’t want to be broadcast to, they want to be part of the conversation, » she said.

« From a unit economic level, per capita on YouTube today, creators with over 500.000 subs will post 1 video per week at 5 minutes in length, » said Rogoway. « The time per fan you’re capturing is maybe 5-10 minutes per week. It’s such a small percentage of the amount of time that fan has. And superfans, you can’t satiate their thirst enough. » Engagement essentially becomes the most crucial currency.

« You can’t create products for people until they’re super engaged, » said Ekstract of License! Global Magazine. « The products have to make sense, the brand extensions do too. You really have to have the fans want the product. But the beauty of social media is that fans will tell you what they want. When we were just in a linear world, there really wasn’t a way for fans to say, ‘Hey, we’d love to have a fashion line from you’. » In short, social media’s direct line to the pulse of passion makes it a lot easier to merchandise talent.

Community is also critical to scaling. « Take a leap of faith and empower fans to create content so they can produce for you during your downtime, » Rogoway went on. « Whether you’re a digitally born creator, or you’re a TV show going a week or more in hiatus periods, what’s that new water cooler? »

The next session was eSports, The Next Big Content Play? Moderated by CEO and co-founder Peter Warman of Newzoo, it included James Glasscock, svp business development and Machinima, and Laurence Jones, commercial director at Endemol Shine Group.

Newzoo is something like a comScore of esports, and Warman kicked off with stats about what esports looks like.

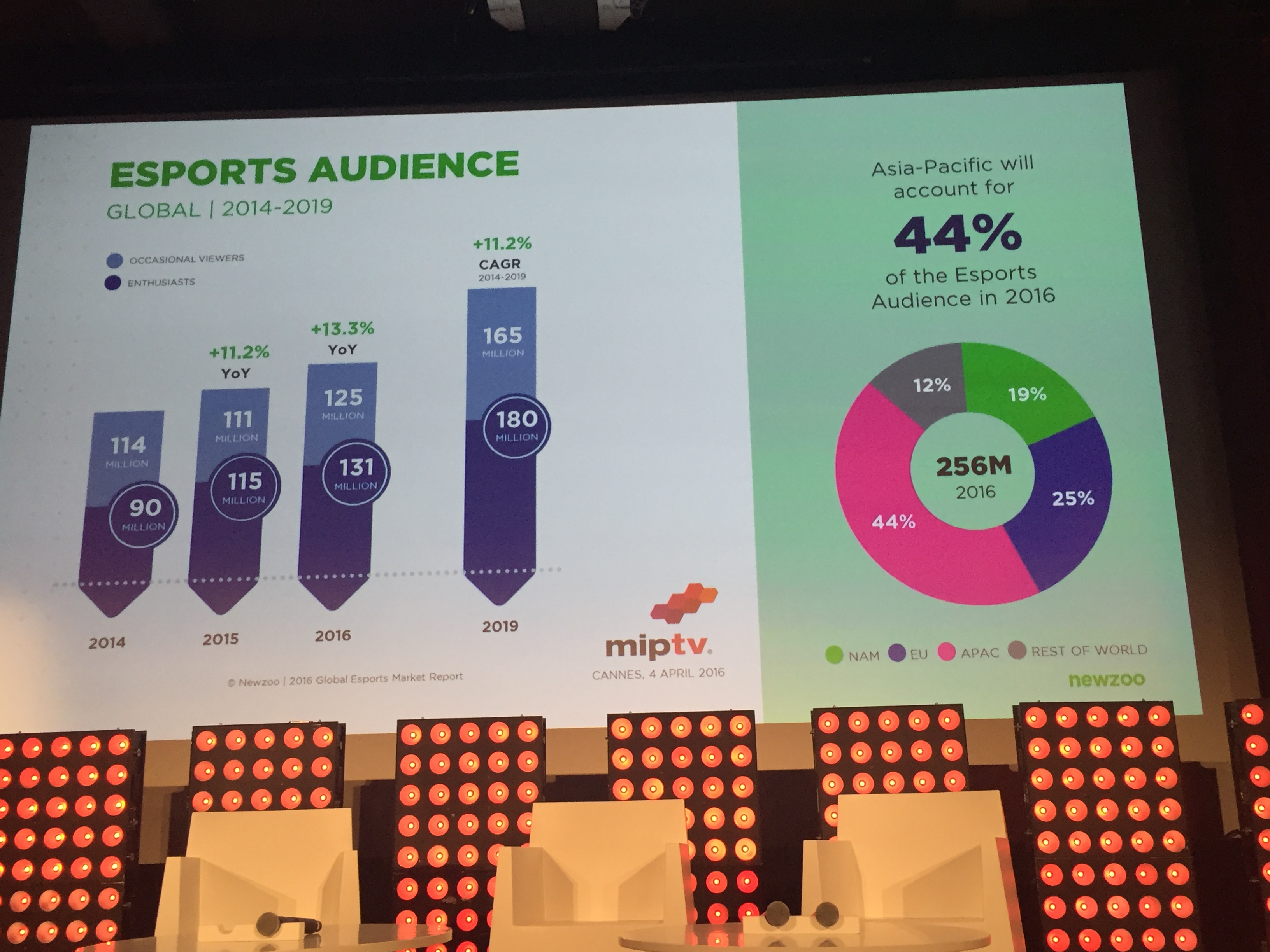

Esports is a sports segment in which pro-gamers engage in live competition. In terms of audience, Casual Viewers in 2016 account for 125 million people worldwide, while Enthusiasts—those who play in addition to watching esports games livestreamed online—total 131 million. By 2019 these figures will rise 11.2%—to 165 million and 180 million, respectively. Asia Pacific currently accounts for 44% of the esports audience.

As in sports, a large amount of the esports audience spectates and doesn’t play. « That audience skews older, richer and has families, » said Warman, breaking down one stereotype people assume about the sector—that it is primarily young, male and a bit skint.

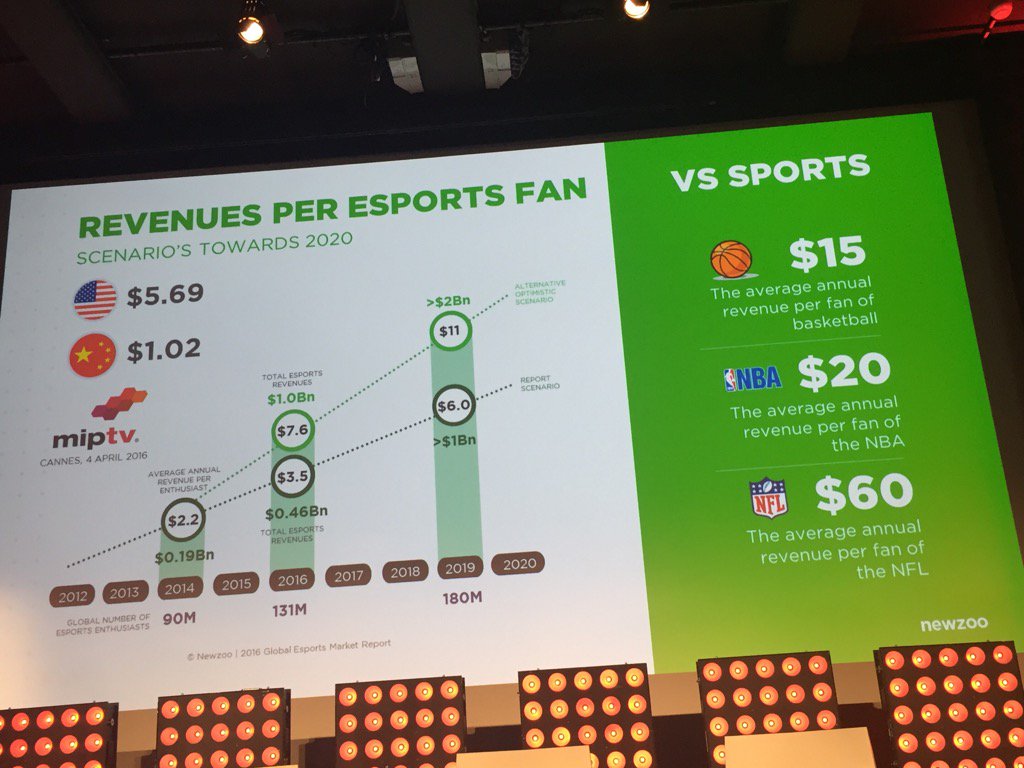

Speaking of, revenues per fan are also rising. Currently fans spend an average of $3.50, which is expected to yield global revenues of $0.46 billion this year, or a full one billion in the most optimistic estimates—meaning it’s rapidly catching up to traditional sports spend (which has the advantage of years on the esports sector, as well as a fully mature merchandising and advertising economy).

But these numbers are not up to date, as Warman observes: « We’re going to hit $1B sooner than we realise, » he admits, because NewZoo did not account for major networks, like the BBC and Turner, beginning aggressive industry investments as soon as this year.

« Lots of game companies are suddenly building extra divisions on esports to monetise the viewing audience, » Warman went on. « There’s no escaping that the interactive media space is heading that way at an enormous speed. And interest from broadcast media is growing as well. Everybody has their own approach. » Game developer Blizzard, creators of the young and popular game Hearthstone, recently « hired a big media guy to help them become the ESPN of esports, » he added.

James Glasscock of Machinima then approached the stage to talk about their numbers, which total 4 billion monthly views. « We’re taking a lot of programming to premium window distribution » this year, he said. Before 2015, Machinima primarily distributed on Twitch and Youtube; moving forward, « you’ll see more premium windows »—as is the case for its web programme Chasing the Cup, which aired on broadcast networks in US:

Endemol Shine’s also released its own esports-tailored offering, dubbed Legends of Gaming, just one example of what the company has planned for this lucrative market, according to Laurence Jones.

While people may be incredulous to learn that millions want to watch others play video games online, 80 million hours of just such esports content was consumed on Twitch alone in one month, per Warman. « It’s a very tribal phenomenon that crosses boundaries. The nature of gameplay doesn’t change regardless of geography, » so people in France can play with people in California; the sector is by nature an international one.

« 300 million fans of esports is starting to rival major leagues like the NFL and NBA in the United States, » Glasscock added.

This is impressive, given that « Gaming has only been around for 100 months rather than 100 years, » said Jones. « Esports is a natural evolution of online multi-player competition. Just because that’s married to the growth of gaming in general, where mobile phones led the way with that, the audience has grown very quickly—so people are slowly noticing. »

Brands are waking up to the opportunity, too. « You’re starting to see the beginning of consolidation » in the sector, said Glasscock. « Modern Times bought ESL and Dreamhack; Turner Broadcasting introduced the e-League, which willl launch in May. Esports starting to take a similar path to other sports leagues in the evolution of sports. »

Except that monetisation will be faster; sports experienced decades of consolidation, with advertisers and corporate sponsors integrating progressively. « In esports, all of that has moved faster, thanks to enabling technologies like Twitch and the internet, » said Glasscock. « It’s a very economical way for advertisers and content distributors to reach millennials. It’s more efficient than more expensive types of traditional programming. »

Building on that, Warman said that Matt Wolfe of Coca Cola—a longtime esports sponsor—called esorts a better investment in terms of effective reach compared to the Super Bowl.

And it isn’t just for guys. « The fastest growing audience of gaming on Youtube is females over age 25. The audience is a lot bigger than male; it’s females and families, » asserted Jones.

Tablet gaming and mobile will also transform the sector. « Mobile has been very disruptive, » said Glasscock, pointing to Vainglory’s recent three-year contract announcement with Twitch. Vainglory, the first-ever purely-mobile esports game, has existed for less than a year. « It’ll be interesting to see how esports evolves on mobile. »

And there’s a lot to be gained by working to help mainstreamise esports, which is still on its quest for its own football—a game anyone can enjoy, even if they don’t necessarily know the rules. Mainstream broadcast will be a big aid. « I don’t see esports disrupting traditional distribution; I see it aligning with it, » said Glasscock.

« It’s about content and context, the relationship between pro-gamers and fans, pro-gamers and fans and the game itself, » Jones added. « Broadcasters must identify how they’re going to tell a story and what story they’ll tell. They must commit to and own that arena. We’ve got a challenge to work out how we tell that story. It’s exciting. »

Your biggest partner in this respect may well be the publishers themselves. « That’s how you’re gonna produce the best content, » said Glasscock. « Some are more hands-on than others. Riot is very active in managing their IP. Activision is taking a similar path, whereas Valve partnered with Turner for their e-League on TBS. It’s unclear what’s the right model; there’s always something to be said about focusing on the core business. At Machinima, that’s what we do: Our core business is storytelling. We think publishers appreciate that. »

He encouraged interested parties to get educated before jumping in, and reinforced the opportunity to reach young male audiences at a low price point. « The sponsors who put their money on the table and started participating have already recognised this and are doubling down. »

« Identify and target the genre and game you feel is appropriate to you, use a mix of media approaches, » Jones added. « Go for it long term, talk to the community, to the games. »