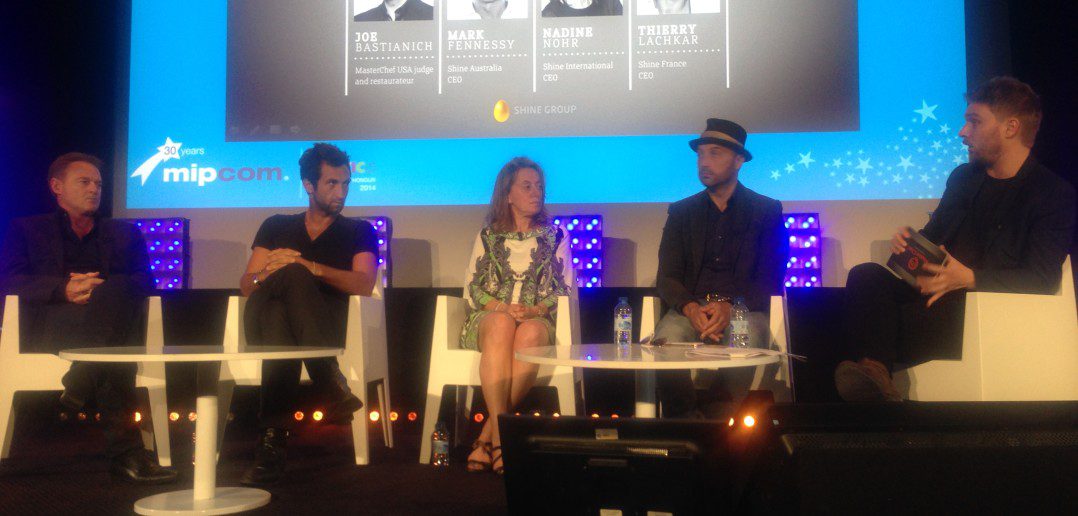

Left to right: Mark Fennessy, CEO, Shine Australia; Thierry Lachkar, CEO, Shine France; Nadine Nohr, CEO, Shine International; Joe Bastianich, restauranteur, critic & judge on MasterChef, MasterChef Junior and MasterChef Italy; moderator Peter White, international editor, Broadcast.

A decade ago, MasterChef relaunched in the UK with Shine. It’s now a global phenomenon with over 45 international versions responsible for almost 200 series. This afternoon, a global bevy of MasterChef execs—and one judge—joined forces to discuss MasterChef’s trajectory and whether the world is ready for more. A few highlights follow below.

In an example of how the MasterChef format evolved from country to country, CEO Lachkar of Shine France recounted, « We were only four people working at Shine France when we sold MasterChef to TF1. You can imagine the pressure. »

The format ended up being similar to others, but « we wanted it to be French as well. »

The differences lay in the cooking elements. « We like to believe our ways of cooking are different from America or Australia—even if it’s not necessarily true, » he said modestly, so the goal was to make the cuisine look « very mainstream » to the French consumer.

It also had to be « very positive »: On MasterChef France, the priority was to choose contestants « keen on changing their lives, not just looking to be part of a TV show ».

This is in contrast to MasterChef Morocco, where that type of aspiration doesn’t work. « Visually we try to keep the same level of production values, » he said.

After four series runs on TF1 and two editions of MasterChef Junior, many old contestants have become chefs, « and in that way it’s been a real success, » Lachkar beamed.

But there’s hardly time for rest. « France is one of the most saturated markets for cooking shows. Most have been successful so far, so it gives us another interesting challenge—we have to change the show for future series, » he said.

« To me the DNA of the format is to be the biggest cooking show ever for non-professional contestants. » The crucial thing is that the dishes are the kinds people can do at home, Lachkar reiterated.

Bastianich also talked about his experience as a judge in multiple MasterChefs and markets. « It’s been an amazing journey; MasterChef is a big part of my life, » he said, adding that he feels Italy and the US—two countries where he’s served as judge— are the two best MasterChefs in the world.

« They’re so different, » he said. « In America it’s hugely successful because it’s very American; in Italy it’s hugely successful because it’s very Italian, » where it’s even changed how people speak: « Terms people use, even mistakes, are in the vernacular. Inscription to cooking schools is up 50% there. »

The social impact is significant, meaning « MasterChef is so much more than a show about cooking, it’s about aspiration and how you can change your life through your passion for food, » said Bastianich. « Being able to execute that story is as crucial to MasterChef as good production. »

But as in France and Morocco, the Italian and American formats are similar but unique. America is classically « big », with « high entertainment values, » Bastianich said. There are also a lot of different cultural foods to work with, from sushi to barbeque to New Orleans cuisine, whereas in Italy they’re obliged to remain within the parameters of Italian food.

On November 4, Fox will premiere Season 2 of MasterChef Junior, which Bastianich calls a « game-changer » and « the single proudest piece of TV that I’ve ever been involved in. Remember one name—Abby—and think of me when you watch it. »

Here’s the Season 1 trailer for MasterChef Junior:

For MasterChef Junior to work, « We have to treat the kids like adults, » said Bastianich. « That tough love scenario we have with them is what makes the show so incredible. The kids are great for TV because they’re honest and unfiltered, most of them cook better than the adults, they’re competitive, they want to win, and they’re cute. »

« Why would that not work anywhere…? » CEO Nohr of Shine International quipped.

The tough-love approach doesn’t work everywhere, though. Bastianich’s mother, who judges MasterChef in Italy, observed a big difference in how children are treated. « In Italy the culture dictates that children be physically nurtured. There isn’t that Anglo separation between children and their taskmasters or adults. They’re more in treating them the way Italian families would treat them. The American way couldn’t work there. »

Bastianich also cites an enormous appetite for more MasterChef all over the world. « You can feel the hunger on social media, » he said. « People just can’t get enough. It’s that whole concept: Leave ’em hungry, don’t overfeed them. »

CEO Fennessy of Shine Australia, however, cautioned against overdoing it. « There’s the temptation to increase the hours, then have a variant, and another series, one after the other. I think it’s great to have; it’s a journey for the viewer. There are other places you can take it, but you don’t want it to be at the expense of the authentic MasterChef, » he stressed.

As an example, Fennessy said that in Australia they only air MasterChef Junior every two years. « The kids are amazing. But it’s really about keeping it authentic for the sake of longevity, » he said. « It’s a beautifully-crafted format, a celebration of life through food. You have to resist the temptation to try to overdo it. »

Bastianich remained bullish. « I’m a waiter. I come from restaurants, » he said. « I can tell you that you got to leave them wanting more, and in my experience of Italy and America, I don’t see an end in sight. »