As the habits of audiences continue to evolve from traditional to digital platforms like the internet, tablets and smartphones, content producers also need to commit their resources to understanding these platforms and the ways in which audiences can engage with content through them. To better serve our audiences, we producers need to evolve the language of ‘new media’, which is, in many ways, the conjunction of every medium.

This change is different from those, which followed from the advent of cinema, television and the internet. The medium of new media is not specific, like film was before the invention of the TV, to the platform itself. The age of multiplatform media is defined by audience behaviour. Previously, television dramas were written to a strict format; they were sixty minutes long with cliffhangers built in to precede ad breaks every eleven minutes. Today, people tend not to watch live broadcasts of these shows. They record them digitally or watch them on their iPads. It doesn’t make sense to adhere to the language of television when the needs of most viewers have little or nothing to do with linear broadcasting.

This is not to say that the language of television should be scrapped entirely; indeed much of the content produced for multiplatform productions still mimes the templates of TV. But the producers of the digital age are no longer constricted by ad breaks or broadcaster’s schedules. Viewers can watch three episodes in a row without one ad break using on demand devices or series DVDs. To serve, as well as anticipate, the needs of our audiences, we need to pay attention to these new behaviours and evolve the language of the medium along with the way we tell stories.

Historically, new media has always borrowed a compositional language from established media; radio and cinema borrowed extensively from the stage, while television drew its formatting from newsreels and serialised pre-rolls. As a new media matures and conquers audiences, it tends to develop a completely novel language specific to its format.

Webisodes and mobile digital content still borrow most of their structure from television. Most of the time the content that’s consumed on these platforms is in fact repurposed TV shows, broadcast in their original formats, or chopped into shorter segments. However, as audiences become increasingly sophisticated, more and more producers are realising that repurposing content for the web is not the correct approach.

Now we’re seeing major TV shows, films, and video games launching spin-off web series, mobile or companion tablet games, digital comic books and ebooks. Creators and writers can expand stories and characters to new platforms, extend plot lines and develop back story, without being confined to conventional arcs, formats or running times of conventional television and film productions.

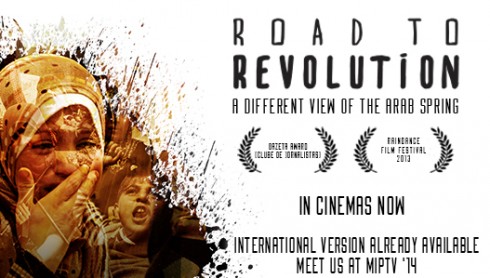

Taking this into consideration, when we faced the challenge of what to do with 200 hours of footage from the shoot of our Arab Spring-based documentary Road to Revolution, we tried to identify the best media and formats to show the different parts of the story. The documentary focuses on the story of the people who lived at the Arab Spring. It’s an emotional portrait of people affected by the revolutionary movement, like the mother who lost her son in the Libyan civil war, or the Egyptian who still resists in Tahrir Square.

Road to Revolution includes a theatrically released feature film, two TV documentaries, 40 webisodes and an app for tablets and connected TV devices that extends the documentary experience. The interactive application provides additional content, including material not used in the documentary, and additional life stories. It also gives an overview of the socio-economic, geographical and political development of each country and ethnicity. With this approach, we were able to create distinct experiences for different screens: cinemas, TV, web and tablets, each with their own purpose, but all complementing each other.

Most of the above content would not have conformed to the rigid format of a 52 min doc slot, but some of the content has proven ideal for both the digital platforms and offline media we chose. These alternative formats and new language aporias are also crucial in building a fan-base that is more intimately connected with our characters and stories. Even though transmedia requires writer-creators-editors to do more work to produce additional content, it affords them with the creative freedom to tell the stories they want to tell.

Nuno Bernardo is the founder and CEO of TV, film and digital production company beActive, and a regular contributor to MIPBlog. He is also an Emmy nominated writer-producer and the author of The Producer’s Guide to Transmedia and the forthcoming Transmedia 2.0 books. Find him on Twitter and Facebook; and meet him at MIPTV!