Photo: Netflix’s season 2 of political series House of Cards is just one more step towards the entertainment industry’s future

What if traditional television was a country facing an army of disruptive and fearless invaders, and big money the only thing left standing between them? Let’s pursue the metaphor by taking a closer look at the « barbarians », or disruptors, and the way their strategies regarding monetisation and other issues have evolved since our last review.

The long-awaited season 2 of Netflix’s acclaimed political series House of Cards (photo) was released on February 14, sparking even more conversation about the giant streaming service’s model and its quest for original content. Who could have predicted this two years ago? House of Cards’ executive producer Dana Brunetti even told Fast Company it was one of his « B teams » that initially met with Netflix, when the company hadn’t even started producing original shows.

Three years on, Netflix has won the « battle of the binge » – proving that the audience is ready to watch a full season in a very short period of time – and become a « TV powerhouse », as Salon points out. CEO Reed Hastings, chief content officer Ted Sarandos and House of Cards star Kevin Spacey even made Fast Company‘s list of 1000 « Most Creative People in Business » in January. Not to mention Netflix’s expansion projects in Europe – especially in France and Germany – spotted by Gigaom.

With such a bright future ahead, what obstacles could possibly face the big red disrupter? On the technical side, Quartz notes that primetime download speeds over some of USA’s biggest internet service providers have declined in the past few months because of ‘peering’, an alternative internet transit system that is not subject to net neutrality rules. Moreover, Netflix’s recommendation tool is taking a leap forward to « deep learning », « a branch of artificial intelligence that seeks to solve particularly hard problems using computer systems that mimic the structure and behaviour of the human brain », according to Wired.

But what if streaming’s future was already doomed by an overabundance of services and content? Wired stresses the difficulty for viewers to have a totally passive and lean back experience with their smart TVs and streaming subscriptions: the very need to choose what to watch contradicts « the simple joy of channel surfing ». In other words, « Netflix is great when you want to watch something, but it’s terrible when you want to watch anything. » Do Netflix and its competitors need proper channels on their interfaces, classified by genres?

One the financial side, two major news in the past few weeks have shown that more than ever, big money is key in the entertainment world if you want to remain a giant: Netflix intends to spend $3 billion on content in 2014, and around $6.2 billion on content over the next 36 months, Gigaom reports. The second major announcement is of course Comcast’s deal to buy Time Warner Cable for $45 billion, creating « a video and internet juggernaut » that is already causing fear among media watchdogs and consumer activists, according to The Los Angeles Times.

Even Twitter, which released its first quarterly report as a public company, has to focus more and more on financial issues in the TV world, in order to grow and monetise itself. Fast Company analyses the various ways the social media platform can create revenue, including Amplify, Twitter’s multi-screen advertising product and « an ingenious way for Twitter to turn their mobile app and homepage into the platform on which fans comment on sports matches, award shows, and television programs in real time. »

Second screen may be a tool to revive reality TV in particular: networks and announcers are anticipating the rise of « gamification ». To quote but one example, Asahi TV Corp. and content-fingerprinting specialist Vobile Japan partnered last year for an unscripted primetime series featuring fish harpooning, allowing viewers to use their smartphones to do some spearing of their own, Variety reports. Gigaom goes further and claims that if this kind of viewer experience improvements doesn’t spread, « social TV is dead »!

The problem is, some experts doubt internet’s ability to attract as many announcers as traditional TV, just because « in our age of ultra-fragmented media », only big TV events like the Super Bowl can guarantee high-volume impressions, whereas « digital impressions are mostly defined as 50% of an advertisement viewable for one second, and there’s not even clear consensus on that », as Mediapost explains. That view is challenged by big data software company Pixability, which praises the assets of online video’s audience precision on VideoInk:

« Smarter marketers and brands are starting to recognize that the pre-purchased, raw impressions so prevalent in television lack both the economies of YouTube auction buys and the target audience precision. »

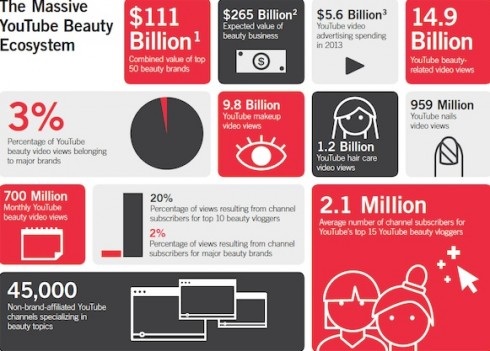

If you top that with Pixability’s study showing that YouTube beauty personalities and vloggers who create beauty content are clearly preferred by online video viewers – major brands garner only 3% of the 14.9 billion beauty-related video views on the video platform – it’s no surprise that online multichannel networks just got their own trade organisation. GOVA (the Global Online Video Association), which aims at bringing more advertisers to the medium, Adweek reports. See « The Massive YouTube Beauty Ecosytem » infographic published on ClickZ below:

Apart from monetisation and engagement improvements, where is TV innovation these days? The answer may come from companies like video camera maker GoPro, elected by Fast Company as the world’s most innovative company in advertising, « for letting everyone in on the extreme-sports video action » via viral hits, an enthusiastic cusstomer base encouraged to share all their creations online, and an in-flight TV channel, not to mention the GoPro digital channel to be introduced to Xbox 360 and Xbox One later this year, as Engadget points out.

It’s not just about equipment makers: Tech.eu explains that Rovio, the Finnish company behind the Angry Birds franchise, has media expansion projects in mind as well, but with a clear educational intention. Last but not least, the future of content may lie in the hands of fastfood chains like Mexican brand Chipotle, who financed Farmed and Dangerous, a whole new TV show to be launched on Hulu this February. The innovation here consists in being « heavy on the brand values »and « light on the product placement », according to Fast Company. The future of branded entertainment on TV?

Hollywood’s way to resist so many disrupters is very subtle, and may be unconsciously inspired by… the Roman Empire. In a brilliant post, Slate demonstrates that the entertainment industry « doesn’t fight off invaders », but « sits down and does business with them. » That should explain, for good, the longevity of an ecosystem that « won’t be disrupted, so much as refocused and rebranded » by the likes of Netflix, YouTube, Hulu, and all the startups that come along. The Empire doesn’t need to strike back: it’s already buying its invaders out little by little.

Discover more TV industry knowledge on our TV Biz News page, where the hottest business developments are curated by the MIP Markets team, via scoop.it…